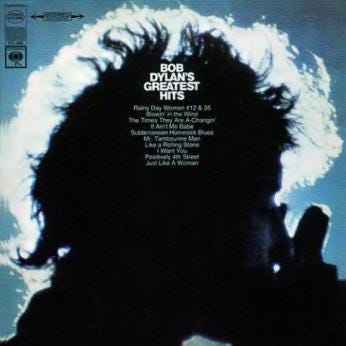

OK, right off the top, here’s the photograph I want to talk about. Earlier, I mentioned in these pages Dylan’s appearance on the folk scene in Newport, 1963.

Back in 1967, this picture won a Grammy for Best Album Cover. It’s already been discussed quite a bit over the years: in interviews, in the movie about me, “Eye on the 60’s,” and even in a chapter (one of many) in a book of Dylan stories called “If You See Him, Say Hello,” by Tracy Johnson.

NOTE: The GRAMMY Awards, which began as The Gramophone Awards, first took place in 1958. The Academy Awards, also known as the Oscars, and The Emmy Awards both recognized the leading artists in film and television, but no such musical equivalent existed. Following the Hollywood Walk of Fame project, which began in the 1950s, a renewed interest in music and the recording industry led to the creation of The GRAMMY Awards as a way for the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences to honor the music industry’s most talented composers, songwriters, and musicians.

After Newport, I didn't think much about Dylan or his meteorically rising career. I still liked Peter Paul and Mary's version of "Blowin' in the Wind," and besides, the country was awash in despair after the JFK assassination in November. And such was my personal despair, as the man who enabled my career was dead, I was practically ready to give up photography.

Then, in February, the country was importantly shaken out of its mourning by the arrival of the Beatles, whose brilliant harmonies awakened us to the fact that life was for living, and we had to move on. The "British Invasion" and the musical responses of new American and international groups and soloists opened the doors to an avalanche of wonderful new music--the "swinging sixties"--about which we'll discuss further in coming stacks.

Dylan, his "electric" breakaway from his folk music fully operational, played two different sets at every concert. He opened with his solo routine, and his second set quintet of rockers, which became the focus of his ever-growing thousands of fans. I didn't know any of that. The Coliseum was so close to our apartment, it would have been foolish for Joan and I not to go. Our seats were okay, sort of mid-orchestra, but I could see, with spot hitting him, the the shot I needed had to be made from backstage. I said, "I have got to get back there." When I tried, of course I was informed that such a thing was off limits. I said, directly and with all the official muster I could impart, employing some of the best bullshit I ever used: "Out of my way bud. LIFE magazine needs this shot and I'm here to get it right now." I had no assignment, or a press pass, but truthfully I had just had a few pages in the mag and may have mentioned that. OK, they said.

Dylan was in that dirty blue spotlight, doing some song I can no longer remember. I put the 300mm lens on him and I could se the whole thing: his hair, his harp, and his halo--the three H's. No motor or anything. I thought: "it can't get better than this." I didn't hang around. I said, "Thanks," and went back to watch the rest of the concert.

When the film came back and most of it turned out pretty darned good, I took the little stack of slides to Columbia Records in New York. The Art Director, John Berg, was a pal of my sister Betsy. He and I had met on Cape Cod a few summers before. When I got to his office, he picked up the first slide. and said, "That's the next cover."

This happened faster than it took you to read that sentence. For the cover, John flipped the image so it seemed Bob was looking forward, and cropped his head to simplify better the shadowy shapes. It looked like a winner. Everything should be that easy!

There was one problem: Bob HATED the picture, and had veto rights for the use of his image. Everything was on hold for a while, while they tried to get him to agree. No soap. So how did the cover even happen? Soon after this concert, Dylan had his famous motorcycle accident and didn't perform for a year or so. During that time, his contract had lapsed and he couldn't stop Columbia from releasing the Greatest Hits album. And I got a check for 300 dollars.

When the award list was announced, Berg telegraphed that we might be up for an award, did I want to come to New York and be there for it? Nah, it was cold and snowing in DC and pretty cozy in our little townhouse. I passed. Next morning I received another telegram from John, saying we'd won. Soon, a little package containing the award showed up at my DC apartment, friends were amazed and loudly buzzing about it. “Wow, a Grammy!” Do you know how cool that is?” “It’s like the Oscar!” “You must be very proud, and excited.” Well, I guess I was sort of proud, in a way. What were the Grammy’s anyway? What meager excitement did exist dissipated completely the minute I opened the box. Inside was a light, plastic cube with the cone-shaped gramophone broken off among other crumpled pieces and my name misspelled in bronze. It was the kind of award one might get in a 4th grade bowling tournament, and you came in second.

I packed the pieces back into the box and returned it with a note saying, “Thanks for this, but please replace it with a whole one, and with my name spelled correctly.” I waited for a response from the National Academy of Recording Arts. Nothing. In fact, nothing for thirty five or so years. By that time I had been living in Alabama, and the "humorous" story of the crummy broken Grammy reached the ears of a nice guy I knew who played the tuba. Tom Dameron is his name, and he knew someone at Grammy HQ and said he might to something to mollify the story.

A couple of weeks later a heavy, large box showed up and in that was another box, purpose-made to hold the new, official version of the vaunted Grammy. It was, and is, beautiful. The Grammys had become big time and enhanced their image with better, heftier awards. This treasured item is now in my office.

FOOTNOTE: A few years later, John Berg told me this story: Greatest Hits Vol 2 came out with a cover a near dupe to the winning one that Dylan had rejected. “You little bastard,” Berg said to Dylan. “This is just like the one you griped about before!” Dylan sort of shied away and sheepishly hid behind his collar. I guess he realized how wrong he was.

Steven Stills in Collins apartment is also an amazing glow picture of yours

Nolan I treasure my copy . Maybe send a selfie of you holding it for me ha ha ha.